It’s common for many Americans living overseas and grappling with annual US tax returns to consider renouncing US citizenship.

While factors like taxation often play a significant role in the choice to renounce, many expats also find themselves caught between the obligation to file taxes and the lack of knowledge to navigate the system effectively.

In the following guide, we seek to clarify the implications of renouncing US citizenship, dispel the confusion1 surrounding expat tax obligations, and empower you to make an informed choice that aligns with your unique circumstances.

Let’s explore what happens when you renounce your US citizenship, starting from the beginning.

Why do some Americans renounce their citizenship?

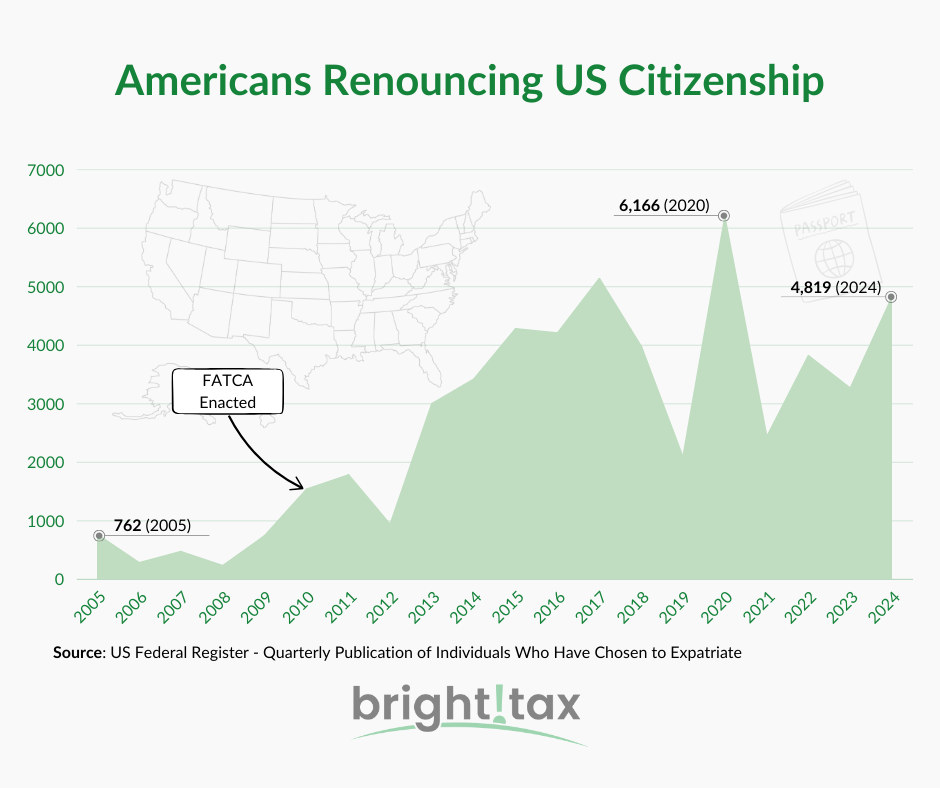

Americans worldwide renounce their citizenship for different reasons. However, one of the top factors driving the surge is the US’s citizenship-based taxation system. This archaic and little-used system requires American expats to declare their worldwide income and file US taxes, no matter where they live.

Complicating things further, annual filing obligation tends to increase in complexity the longer a US taxpayer remains abroad due to the filing complications associated with milestones such as buying a home or the birth of a child.

Additionally, many cite the US’s harsh tax and anti-money laundering regulations, such as FATCA and FBAR, as reasons for citizenship renunciation. These regulations can be a source of headaches and frustration, particularly without professional guidance.

How to renounce US citizenship

You’ll go through a five-step process if you want to renounce your US citizenship.

Step 1

Obtain a foreign passport: You’ll need citizenship in another country to begin your US renunciation. You don’t want to be left stateless with no country to reside in legally.

Step 2

Consult with a tax and immigration professional: Speaking with an immigration professional will help you fully understand the process and result of giving up your US citizenship. On the tax side, you’ll want to understand and plan for the tax implications of the decision.

Step 3

Complete the paperwork: Fill out the following linked renunciation forms, but don’t sign them. You’ll sign them at your renunciation appointment.

- DS-4079, Request for Determination of Possible Loss of United States Nationality

- DS-4080, Oath/Affirmation of Renunciation of Nationality of United States

- DS-4081, Statement of Understanding Concerning the Consequences and Ramifications of Renunciation or Relinquishment of US Nationality.

- DS-4082, Witnesses’ Attestation Renunciation/Relinquishment of Citizenship, and

- DS-4083, Certification of Loss of Nationality of The United States

Step 4

Book your renunciation appointment: You can book your appointment at any US embassy or consulate. Appointment wait times can be very long, so it’s wise to plan at least six months in advance.

Step 5

Attend your renunciation appointment: Bring your completed paperwork on the day of the appointment. In addition, make sure you bring:

- Your most recent US passport (or US birth certificate if you don’t have your US passport)

- All of your current foreign passports

- Evidence of any name changes (if applicable)

- Funds to pay the Renunciation Fee.

Step 6

File your final tax return. This is the final step. In addition to filing a “Dual-Status” return to report both the part of the year you are a citizen and the part of the year you are not, you’ll include Form 8854 as a statement of expatriation when filing your final tax return.

How much is it to renounce US citizenship?

The Department of State in January 2023 announced the government’s intention to reduce the Renunciation Fee from $2,350 to $4502. However, the changes have not yet gone into effect. For now, the Renunciation Fee remains at $2,350.

*Kindly note: our team will update this article should anything change!

Renouncing US citizenship taxes

American citizens abroad, or Green Card holders, may view citizenship renunciation as the answer to escape US tax compliance.

However, renouncing US citizenship is not a get-out-of-jail-free card where taxes are concerned. When you file to renounce your US citizenship, you’ll need to ensure that you’re caught up on the past five years of US filings. Depending on your net worth, you may also be subject to an exit tax.

The exit tax isn’t a penalty for leaving the US (although, in all fairness, it may feel like one). Think of it as your final bill for your unpaid future tax debt that the IRS wants a share of ahead of schedule.

The difference between covered and non-covered expatriates

When assessing an applicant’s file for citizenship renunciation, the applicant is categorized into one of two categories: covered and non-covered.

What is a covered expatriate?

A covered expatriate must be a US citizen or a long-term resident.

For clarity, a long-term resident is generally3 someone who has been a lawful permanent resident of the United States for eight of the last 15 years immediately preceding the renunciation application.

In addition to being either a US citizen or a long-term resident, the law will classify you as a covered expatriate if you meet any of the following three conditions on the date of your expatriation:

- Your average annual taxable net income over the previous five years exceeded $201,000 for the 2024 tax year (this will increase to $206,000 for the 2025 tax year)

- Your personal net worth is $2 million or more on the day immediately before expatriation

- You haven’t filed all the required tax returns for the previous five years leading up to renunciation

Exit tax

Also known as expatriation tax, exit tax is the tax covered expatriates pay when they renounce their US citizenship.

As a covered expatriate, you renounce US citizenship and exit Uncle Sam’s jurisdiction. Generally, the IRS will look at the fair market value of most of your assets, calculate any capital gains, and charge tax as if you had sold them all on the day before you gave up citizenship.

Exit tax calculations can get complex quickly depending on the types of assets you own at the time you renounce.

Gifting as a covered expat

If you’re a covered expatriate and you grant someone in the United States a gift whose value exceeds the annual gift tax exclusion limit of $18,000, you may need to file a gift tax return on Form 709.

⚠️ Important to note:

Individuals who renounced their US citizenship or ceased to be lawful permanent residents of the United States on or after June 17, 2008: If at the time of renunciation, you were a covered expatriate, there are potentially serious tax implications on any future gifts or bequests you may bestow to an individual who is a US taxpayer. This pending regulation is IRC section 2801 and its imposition is currently deferred. (4)

Non-covered expatriate

A non-covered expatriate, on the date of expatriation, has:

- A net worth of less than $2 million on the date of expatriation

- An average 5-year annual taxable income of $201,000 or less

- Filed all required tax returns for the previous five years.

Income tax debts

To renounce your US citizenship, you must have a clean bill of tax health.

That means you must have filed your tax returns for the previous five years and paid any outstanding tax debts.

Despite the cut-and-dry nature of the requirements, many expats know firsthand that fulfilling IRS obligations is not always straightforward. For example, what if you have not filed some or all of your US tax returns in the past five years? Fortunately, the IRS has two sets of procedures in place that anticipate this sort of scenario.

Streamlined Filing Procedures

If you can certify that your failure to file in one or multiple previous years was non-willful (read: you did not know you were required to do so), you can use the Streamlined Filing Procedure (SLP) to catch up. Additionally, qualifying for the SLP exempts you from paying any late-filing penalties – a major win and source of relief for US expat taxpayers.

If you believe you might qualify for the Streamlined Filing Procedures, an expat tax accountant can confirm your eligibility and ensure your application is accepted.

Relief Procedures for Certain Former Citizens

This procedure is for US citizens who have never filed a tax return, such as some Accidental Americans (more information on AAs below). However, the additional parameters for qualification are similar to those outlined above in the SLP section.

In order to qualify for these procedures, the IRS specifically outlines the following eligibility criteria:

- You have relinquished your U.S. citizenship after March 18, 2010.

- You have no filing history as a U.S. citizen or resident;

- You did not exceed the threshold in IRC 877(a)(2)(A), related to average annual net income tax for 5 tax years ending before your date of expatriation;

- Your net worth is less than $2,000,000 at the time of expatriation and at the time of making your submission under these procedures;

- You have an aggregate total tax liability of $25,000 or less for the five tax years preceding expatriation and in the year of expatriation (after the application of all applicable deductions, exclusions, exemptions, and credits, including foreign tax credits, but excluding the application of IRC 877A and excluding any penalties and interest).

- You agree to complete and submit with your submission all required Federal tax returns for the six tax years at issue, including all required schedules and information returns.

How long does it take to renounce US citizenship?

Renouncing US citizenship can take up to six months once you’ve had your appointment at the US embassy. However, many embassies are currently heavily backlogged due to the shutdowns that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the current high demand for renunciation services. Therefore, expect the process to roughly take between six months and 1.5 years from start to finish.

Is renouncing US citizenship the right decision for you?

Assessing the pros and cons of renouncing US citizenship will likely take time and research.

Although there are many factors to consider, one of the most important determinations to make is whether you’ll be categorized as a covered or non-covered expatriate. As we’ve seen, covered expatriates can pay a steep price to leave the US behind. This is because, unlike non-covered expatriates, they’re liable to pay exit taxes.

Ultimately, renouncing US citizenship is a highly personal choice. Deciding to renounce should be decided with social, financial, educational, religious, and even health considerations in mind.

References

- Citizenship Renunciation – 5 Common Myths

- Fee to Renounce Citizenship to Drop

- Do Non-Green Card Years Count Toward the 8-Year Long-Term Resident Test?

- Gifts from Foreign Person – IRS

- Renunciation of US Nationality Abroad

- Your Payments While You Are Outside of the United States

Renouncing US Citizenship as a US Taxpayer Abroad - FAQ

-

If I renounce my US citizenship, can I get it back?

According to the IRS webpage that discusses renouncing US citizenship abroad, “… those contemplating a renunciation of U.S. citizenship should understand that the act is irrevocable, except as provided in section 351 of the INA (8 U.S.C. 1483), and cannot be canceled or set aside absent a successful administrative review or judicial appeal.” (5)

-

Do I still have to file US tax returns if I renounce US citizenship?

After your US citizenship renunciation is complete, you will no longer be required to file US tax returns to report your worldwide income. However, before you go, you are required to file a final US income tax return, which will be for the year you renounce your citizenship.

And while you’ll declare all the income earned during the renunciation year, whether earned when you were a citizen or not, you’ll only pay taxes to the IRS on the portion of worldwide income earned when you were still an American citizen.

Once you’ve renounced, you are subject to tax on US source income only, just like any non-citizen taxpayer would be. Some common examples of this are if you have a US-based rental property, dividends in a US company, or if you spend time working in the US and earning income on US soil.

-

Can you live in the US after renouncing US citizenship?

In theory, yes, but in reality, it won’t be as simple as re-entering the US as a US citizen would. Once you renounce your US citizenship, living in the US will require you to obtain a visa. Obtaining a visa is a lengthy and often expensive process, and requirements and the likelihood of acceptance vary from country to country. Moreover, even if you just want to visit the US, the visa requirements attached to your adopted country will apply to you. Only American citizens and Green Card holders have the right to enter and leave the US whenever they please.

-

Can you get a Green Card after renouncing US citizenship?

Technically, yes, and yet in practice this is often made complicated by the fact that any application to obtain a Green Card will reveal to the processing administrator that you are a former US citizen who once enjoyed full US citizen rights. This framing does not position your application especially favorably and may contribute to the rejection of your application for a US Green Card.

-

Will my children be American if I renounce US citizenship?

Even if you abandon your US citizenship, your children are American citizens if they acquired US citizenship at birth.

If you have a child after you have completed the renunciation of your US citizenship, then you will not be able to give that child US citizenship. Instead, they will need to obtain it either by birth on US soil or from their other US citizen parent.

-

Do you lose social security if you renounce US citizenship?

Not necessarily. You will retain your Social Security number and technically still be able to withdraw any benefits for which you’re eligible. However, whether or not those benefits can legally be paid out to you would depend on your country of citizenship and residence. (6)

Connect on LinkedIn

Connect on LinkedIn